The Rules of Disengagement

The following will appear in the Hill Times print edition next Monday, September 20, sans the groovy chart and links. Falling response rates and declining voter turnouts are two symptoms of increased disengagement in the mechanisms that inform and channel collective concerns. In such a political climate, the mandatory census long form questionnaire is a tool that can help keep us on track in the pursuit of good government.

*************************************

“Peace, order and good government†may define us as Canadians, but the last principle in that phrase has never been something that we could take for granted. “Good government†requires an investment of our time and our attention, an involvement that we seem less willing to make today than at any other point in our history.

Call it the new rules of disengagement.

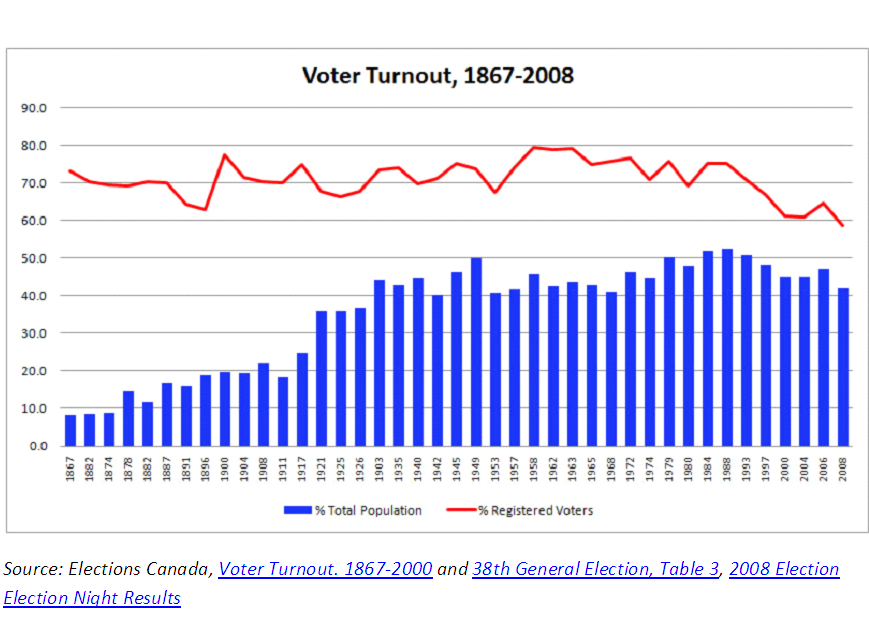

The most obvious place where this malaise can be diagnosed is in the polling booth. Between 1967 and 2004 voter turnout for federal elections was remarkably consistent, hovering for most of that period between 65% and 75% of registered voters. Public interest peaked with the elections of 1958, 1962 and 1963, when almost 80% of Canadians turned up at the polls.

Compare this to the last federal election. When asked to shape their next government in 2008, only 58.8% of registered voters bothered to cast a ballot, marking the lowest turnout ever in Canadian history.

Growing ambivalence and apathy also is evident in falling response rates to polls and surveys, which have been in steady decline since the 1960s, a time that stands as a turning point for Canada and the U.S., not just for social and economic reasons. It marked a change in attitude.

The 1960s are famous for sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, black power, women’s lib, anti-war protests, and student uprisings. If there was a single bumper sticker that captured the spirit of the era it was “Question Authorityâ€.

Flash forward half a century and that attitude has spread like wildfire, and not without reason. Short-sighted and self-interested leadership abounds in public and private spheres alike. An epidemic of cynicism and greed has led to blunder after blunder in decision-making, sometimes with catastrophic consequences. Lack of deference has naturally blossomed in this climate. The notion that, “It’s nobody’s business what I do,†is widespread, even while telling all on facebook.

Attitudes towards big government, big business and big unions have soured as a matter of course. Not much thought has been given to the alternatives. The flip side of broad-based mistrust is the notion that the only one you can trust is yourself. Trouble is, you are not in charge – well not in charge of much, anyway – and your quality of life is shaped by decisions made by big institutions. Those decisions are mostly based on data, not gut feelings. Data is created by asking questions, systematically, methodically. That usually means through surveys, financed by big organizations and institutions.

We want our corporations, governments and non-profit groups to be responsive and expect them to meet our needs in a timely way. That requires reliable, up-to-date information; information collected by someone asking, and our telling.

But response rates to polls and surveys have been falling like a stone over the past decade. In the U.S. there is a whole industry dedicated to improving response rates. At learned conferences, techniques are shared on how to get people to agree to answer questions. (See, for example, the proceedings from this one.) The two groups most pre-occupied with gathering better information in the private sector are marketers and health researchers.

Marketers are used to working with very low response rates. How low is low? The Canadian Marketing Association notes that response rates are typically 1-3% for scattergun direct mail, though it can rise to 25% among current customers. An Industry Canada study noted that it is not uncommon to have response rates of less than 10% to telephone surveys, a finding echoed in a recent presentation to the Marketing Research and Intelligence Association of Canada. Canadian pollsters have seen their response rates drop from 30% to 40% two decades ago to between 10% and 20% today. (From interviews with members of the Marketing Research and Intelligence Association.)

There are two types of people who don’t respond to surveys: those who are too busy, and those who won’t answer questions, on principle. You can’t do much about people who have decided they won’t tell you anything and, through the census affair, the Harper government has actively encouraged people in that group and has possibly raised their numbers. But with time and follow-up you can nudge response rates among those who were just got asked at the wrong time. Ipsos MediaCT reported in 2008 that the average response rate for such surveys was 50%, though that is down from 78% in 1968.

These days health-related surveys garner a better response rate than any other type of private sector survey, around 65%. That’s partly due to follow-up techniques, but it seems we are more inclined to answer questions about our health than just about anything else. Perhaps most of us have a sense that we could be beneficiaries of good health information at some point in our lives. But medical research has shown that even a response rate of 80% can risk the validity of a medical study, depending on who didn’t answer the questions.

What dogs all research is not knowing, both the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns. (Thank you, Donald Rumsfeld.) Non-response bias can pollute findings because the profiles of who does and who does not respond are often significantly different. Research, based on census findings, shows very rich and very poor people are less likely to respond to surveys. So, too, will a voluntary survey capture fewer responses from Aboriginal and Inuit populations, recent immigrants and harried young families.

Marketers aren’t worried about non-response bias because they are increasingly targeting particular segments of society for their surveys, say women aged 25 to 54 with kids under the age of 15, or those with disposable incomes over $75,000. Their objective is to get a quota of responses from a certain tranche of the population, not a representative sample of us all.

But that’s not a strategy that can be imported to the public sector. As Patricia Simmie of Ipsos Reid put it, “It doesn’t make much difference if market surveys have small non-response biases. It won’t change the way we market a new can of corn.†She and other pollsters have made clear, to find out if what they know is relevant, they turn to census findings.

Without these findings, everyone is at sea. In the private sector pollsters, businesses and non-profits are concerned that the Harper government says a voluntary survey can replace a mandatory census. Falling response rates are one thing. Losing a reliable map of the landscape you are operating in, so you can see if you’re really off course, is another.

Since the day-to-day business of government relies on reliable, timely, high quality data and representative samples of the entire population, governments perhaps have the most to lose by relying solely on voluntary surveys.

Compared to private sector results, people are more likely to answer Statistics Canada’s surveys. But, here too, response rates are dropping.

Statistics Canada’s voluntary questionnaire, the General Social Survey, enjoyed steadily high co-operation from Canadians for almost two decades. From 1985 (when it was first introduced) to 2003, the response rate ranged between 85% and 75%. By 2008, there was a precipitous drop to just over 55%. (Thanks to Christopher Barrington-Leigh at UBC for the charts.)

The Survey of Household Spending also shows declining a response rate. Kevin Milligan and David Green, economics professors at UBC, have tracked this from a high of 75% in 1996, to a low of 65% by 2008.

Then there is the Census. In 2006, the response rate on the mandatory short form Census was 97.5%, and 95% for the long-form. No other public survey produces such results.

Statistics Canada conducted an unpublished background study to test-drive the impact of switching from a mandatory census long-form questionnaire to a voluntary survey. Lower response rates led to less accurate results, a problem that could not be resolved by simply increasing the sample size to get more respondents.

As reported on September 9th in the Globe and Mail, the study — entitled “Potential Impact of Voluntary Survey on Selected Variables” — showed that a voluntary survey paints a different picture of Canada by population traits like citizenship, race, language and education. One striking example of differences between the two methods of collecting answers to the same questions was the measured decline of renter households between 2001 and 2006: the voluntary survey reported a 3.08% decline, the census results showed an 8.07% decline. That type of overestimating on how many people are homeowners can lead to all sorts of avoidable public policy blindness on something as basic as housing needs.

This is what we’re up against when it is suggested by the Harper government and others that Canadians voluntarily will provide all the information we need to StatsCan. The evidence is to the contrary.

The way to keep human systems working properly is through a feedback loop. For this, reliable information is essential.

A mandatory census does not just speak to the notion of civic duty; it also speaks to the government’s duty to address and represent the interests of all Canadians, in every corner of the country. The mandatory long-form census questionnaire is a key tool for achieving this goal.

The Harper government has cast the mandatory versus voluntary approach to collecting information as an issue of fundamental freedom. That pre-occupation with individual liberty rings true to more American than Canadian ears. Our expectations are different. Since Confederation we Canadians have sought “good governmentâ€, to meet our needs as individuals and as communities. And for our needs to be assessed, we need not only to ask questions about how we live our lives, but we need everyone to answer them.

That is why the mandatory long-form census is essential. It helps us pursue the “good government†we want, expect and deserve.

I expect that we have underestimated the full effect of muliticulturism. We have invented and manufactured “subversive” immigration by not offering newcomers the oppertunity to learn english. And nor do we offer the poor adequate resources to make something of themselves. Poverty is costly! Look at the infant mortality rate of the poor and the resulting babies that are 43% smaller than the national average. Do not assume that because ESL classes are a bus ride away that they will go. They won’t! Not the new immigrants; nor the ones that pre-dated the switch from the Judeo-Christian model of immigration. I have thousands of old Italian women in my ward that never learnt to speak English [for example] about 20% of new immigrants sit on welfare and roll the wheel of dependance. What has that got to do with a poor voting turnout? Social Cohesion has broken down, and not just with new immigrants. I suggest that the IMF knew this when they started their propoganda to undermine the North American economy. Capital Market Liberalization was built on totally false assumptions and they knew it. But politicians in most every country ate up their rubbish like hungry trout. And now we have the most significant change in economic power in the last 200 years. And no one cares!