Ontario’s Electricity Sector IV: Pre-Election Update

My first, second and third posts on the Ontario electricity sector described how policy and administrative decisions by different Liberal Governments gave rise to excess electricity generation with an inflated cost structure, leading to higher electricity prices. In anticipation of June 2018 elections, the Liberal Government recently implemented a costly and first-in-Canada financial scheme to fund its “Fair Hydro Plan” (FHP) to provide a short-term 17% price reduction. Given that the FHP is now a financial reality, this post focusses on the options available to a new Government with respect to both the FHP and the main driver of Ontario’s inflated cost structure, long-term contracts with independent power producers (IPPs).

Matter #1: What to do about the FHP

Ontario consumers received an across-the-board 25% reduction in electricity prices in July, consisting of 17% from the deferral of certain Global Adjustment (GA) costs and 8% from the rebate of the provincial portion of the HST. With respect to the former, Figure 1 updates my earlier analysis with publicly-available data from Ontario’s Financial Accountability Officer, showing that the FHP borrows about $18 billion in the short term and pays back about $39 billion in the long term. This scheme is designed to lower prices in anticipation of the upcoming election; it does not reduce underlying costs, only defers them.

It is clear that the Liberal Government will continue the FHP if returned to power. While the Conservatives and NDP both voted against the FHP-enabling legislation, neither has yet clearly stated what they would do if in power. The challenge is that the FHP requires the Government to continue to approve borrowing to keep prices below costs for an extended time period for political advantage. Many alternative borrowing schemes with different interest costs and political repercussions could be devised. Figure 2 presents my design of an Alternative Plan that would reduce the total amount of borrowing by about 55%, simply by transitioning back to cost-based pricing soon after the election.

As shown in Figure 3, the difference between the two plans is significant, at over $22 billion in the repayment phases. After a period of artificially low prices, both plans bring prices back to or above costs. The FHP has prices below costs for a total of ten years, the Alternative Plan for about half that time. Once borrowing has to be repaid starting in 2028, the prices under the Alternative Plan would be significantly lower than under the FHP. What would the Conservatives or the NDP do if they were elected in 2018? Would they continue with something along the lines of the FHP that they have critiqued? Or would they take the economically efficient but politically riskier option to return prices to costs faster than in the FHP, perhaps as in this Alternative Plan?

Matter #2 – What to do about the Contracts

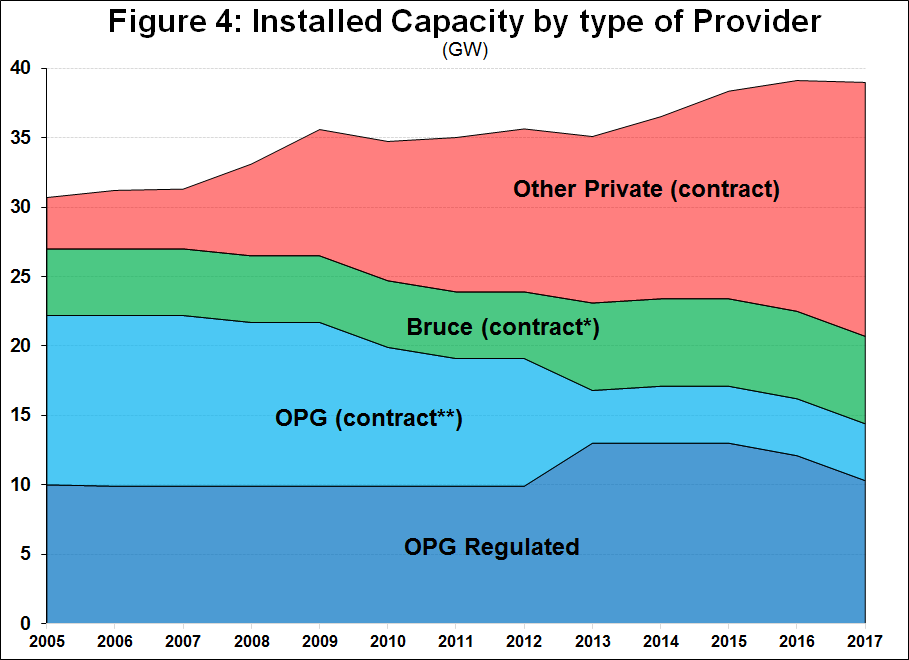

In previous posts, I demonstrated that the main policy driver responsible for Ontario’s inflated electricity cost structure has been the adoption of regulation-exempt, bilateral long-term contracts to procure new private-sector generation capacity. This policy approach guarantees private producers a specific price at which they can sell their electricity, regardless of the market price. Figure 5 shows how installed capacity has evolved over time and how publicly-owned generation under OPG (both regulated and under contract) has declined and been surpassed by contract-based private generation. (The Bruce nuclear facility is a special case, a type of revenue-generating public-private partnership (3P) whereby management and financing is private while the infrastructure remains public; that is now also under contract.)

Has this bilateral long-term contract approach turned out to be good public policy? In the broader context of a political decision to have new generation provided only by the private sector, this approach may have been necessary in the early days of reform in the mid-2000’s to attract adequate private sector financing. However, such an approach soon become antiquated and indeed unique in North America, where other market-driven jurisdictions were implementing more flexible and less costly means to procure capacity. Indeed, in the context of the current Market Renewal process in Ontario, the Government has accepted that one such approach, Incremental Capacity Auctions (ICA), would replace long-term contracts as the means to procure capacity going-forward.

But that policy decision does not address the effects of the legacy 29,000+ long-term contracts totaling about 28 GW that have been signed and for which rate-payers are on the hook for another 10 to 20 years. It is the payment of such contracts that drive future costs; their review is the only means of lowering such costs. To ensure that such a review is a fair and reasonable policy option, it is important to discuss again why many of these contracts were not good public policy, putting these contracts into conceptual context as yet another type of 3Ps wherein the asset ownership and revenues of a traditionally public service (electricity) is private with a revenue stream guaranteed by the public. One of the Government’s stated reasons for the adoption of the private sector contract approach was that the public would not bear the risks of construction cost overruns and delays. That risk was in effect transferred to the private sector. However, these contracts failed to transfer two types of commercial risk, leaving them wholly with the public.

One such risk is associated with excess capacity. In a competitive market with free entry/exit, a situation of excess capacity would not hold for long because the corresponding lower market price would drive higher-cost IPPs out of the market. That does not occur in Ontario under the contract approach because the market price is only a small portion of the revenues received by IPP, the rest being the GA. So there is no exit, and the public continues to pay for unneeded capacity and curtailed electricity.

The other type of risk is associated with the difference between contract versus market price. The long-term cost trends to generate electricity depend on technology, input prices and technological developments. In Ontario, the market price of electricity has been in steady decline since about 2008-2009 (consistent with other competitive energy markets in North America). In the meantime, technological improvements have resulted in a steep reduction in the price of renewables generation. Rate-payers have only benefited partially from these developments. For example, standard offer solar contracts signed in 2009 will mean that rate-payers will continue to compensate IPPs until 2029 at the rate of $800/MWh set in 2009, rather than the current competitively-contracted average price of $155/MWh.

Options

So what are the options available to a new Government interested in reducing future costs by reviewing some of these contracts? First, it is important to create a hierarchy of contracts to understand the task at hand. By way of background, of the 28GW total contracted, OPG and Bruce account for 11GW. Of the remaining 17GW, about 5GW are accounted by about tw0-dozen larger contracts that were negotiated bilaterally, about 6GW were procured by standing offer arrangements (accounting for nearly 29,000 smaller contracts) and about 6GW were procured competitively via about 70+ contracts. This means that about 11GW were contracts that were not competitively sourced and whose contract price was established via negotiation or administratively. I would suggest that it is these contracts that could be first on the list to be reviewed. Second, it is also important to note that their review would not be an easy or fast process (otherwise it would already have been done) and is subject to legal and political risk because these contracts include termination and other compensation provisions if they are unilaterally amended by the Government. The specifics of such provisions, however, like the rest of the contracts, are confidential (at least for the bilaterally-negotiated contracts); therefore, these options are necessarily preliminary, and may have to be revised based on a review of such provisions.

- Option #1. Negotiation. The Ministry could indicate to some IPPs that it wants to re-negotiate the corresponding contracts with the objective of reducing contract prices. The affected IPPs would have to determine whether to participate or to remain shielded behind the termination/compensation provisions and risk the uncertainty associated with the new Ministry proceeding with one or both of the options discussed below.

- Option #2. Cancellation of Contracts with no special additional compensation. The Ministry could cancel some or all contracts, which would mean that the affected IPPs would no longer receive the GA or any curtailment payments, but would revert to the pure energy market of 2002, receiving only the market price (HOEP) for actual electricity dispatched. From the public side, the savings would be significant. Some of the affected IPPs would claim compensation in courts and international fora, and Ontario’s regulatory reputation in the energy sector would be further damaged, thereby further raising the risk-premium for future private investment in the sector. In the context of the current excess capacity, I can see a number of scenarios wherein the long-run public savings would be greater than the corresponding costs, especially if the Government decided to revert to earlier policy of giving primacy to the public sector in any required new investment after the current surplus situation is concluded around 2024-25. A variation of this option is that in tandem to the cancellation, the Government also enacts legislation that shields it from any claims of additional compensation, along the lines argued in this legal note.

- Option #3. Replacement of Contracts with a new regulated regime. The Ministry could amend/cancel some or all contracts, replacing the compensation-related provisions with a new regulated regime. There are of course many options in this regard, but the main principle would be to provide for a regulated rate of return (ROR) for IPPs. One variation of this would be to establish a going-forward IPP-specific compensation regime providing such an ROR over the life of the project. For example, say that the calculated net revenue requirement to earn the regulated ROR for a particular 20-year project is $10 million, and over the last 10 years the project has received $7 million. Without any change, the project would receive another $7 million in the next 10 years, meaning that by its end, the project would have been over-compensated by $4 million in excess of the reasonable ROR (of $10 million). Under this example, the Ministry could revise its compensation regime downwards so that this IPP would receive only $3 million over the next 10 years, for a total of $10 million over the twenty years. A relatively efficient application of such a regime would likely be based on a series of economic models of efficient firms using current technology that could be updated periodically. Such models would be designed with the objective of capturing the majority of the affected IPPs, rather than having to review and calculate the ROR for every IPP. However, the Ministry would also need to carry out case-by-case reviews of the largest contracts and consider any special cases by appeal. My hypothesis is that total compensation to IPPs would be reduced considerably compared to the status quo under this option. It is possible that a portion of the affected IPPs would claim compensation in courts and international fora, but I suspect that it would be fewer than under Option 2, that a lower percentage would be successful and that any damages would be orders of magnitude less than the savings to the public.

There are tens of billions of dollars at stake. The Liberal Government has indicated that they will not review any of these contracts. What would the Conservatives or the NDP do if they were elected in 2018? Free from association with past policy mistakes and alliances, would they try to turn the political spotlight on some of the IPPs to see whether it strengthens their hand in future potential negotiations? Or will they take the well-worn path, throw their hands in the air saying there is nothing to be done (now that they have access to the confidential contracts) and continue to blame Liberal Governments for another generation, while rate-payers continue to pay for those mistakes?