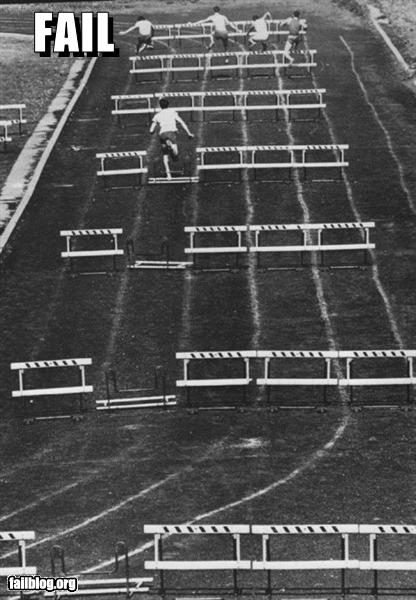

Do Corporate Tax Cuts Boost Investment Over the Hurdle?

Andrew Jackson has engaged perhaps the strongest theoretical argument for corporate tax cuts: that they make more new investments viable by lowering the pre-tax return needed to get over an after-tax hurdle rate of return. (Indeed, I remember the C. D. Howe Institute’s Finn Poschmann lionizing Andrew Coyne for making this argument halfway through TV Ontario’s last post-budget panel.)

Imagine that a corporation needs at least a 10% return to justify making new investments. When Canada’s combined federal-provincial corporate tax rate was 36%, only investments with a pre-tax return of 15.6% or more would have cleared that hurdle (15.6*(1 – 0.36) = 10).

With Jim Flaherty’s target corporate tax rate of 25%, investments would need a pre-tax return of only 13.3% (13.3*(1 – 0.25) = 10). So, recent corporate tax cuts should prompt the corporation to make some tranche of new investments with pre-tax rates of return between 13.3% and 15.6%.

But as Andrew Jackson notes, investments with pre-tax returns above 15.6% would have happened anyway. On all of those investments, corporate taxes were a perfectly efficient and costless source of public revenue. Corporate tax cuts were a pure giveaway that did nothing to improve incentives.

Also as noted by Andrew, pre-tax rates of return are not constant. If there is insufficient demand for a corporation’s output, the potential return on new investments will be close to zero. Public spending financed by corporate taxes can get potential investments over the hurdle by increasing demand and/or by providing needed inputs like infrastructure.

The hurdle rate of return is not constant either. If an investment is financed with debt, then its return must exceed the interest payments on that debt.

Critically, interest payments are deducted from profits in tax calculations. Corporate income tax does not touch the returns needed to cover interest costs and applies only to returns above that hurdle. (As Paul Samuelson demonstrated back in the 1960s, corporate tax does not affect investment decisions if interest is deductible.)

Of course, the cost of equity capital is less clear. But it seems reasonable that investments financed with equity will be made only if the return at least equals any dividends due on the newly issued shares.

For Canadian shareholders, the dividend tax credit refunds all corporate taxes on profits paid out as dividends. So, corporate taxes do not cut into the returns required to justify Canadian equity investments.

Foreign shareholders do not receive the dividend tax credit. But if the foreign shareholder is a US corporation, it ultimately faces a 35% tax rate. Cutting Canadian corporate taxes below that rate does not increase its after-tax returns.

More broadly, other factors like generally low business costs, a well-educated workforce and abundant natural resources make pre-tax returns higher in Canada than in many other countries. As Jayson Myers admits, corporate tax cuts have had no apparent effect on inflows of foreign investment.

Canadian corporate taxes do not decrease returns paid as interest, distributed as Canadian dividends, or repatriated by US corporations. Therefore, corporate tax cuts will not help investments funded by debt, Canadian equity, or US corporations get over a hurdle rate of return.

To a substantial extent, corporate taxes just skim off excess profits from investments that are already over the hurdle. Rather than simply defending corporate taxes as a necessary source of revenue, there is a case to be made that they are a particularly efficient means of raising revenue.

Great work Erin, I am thinking about calling you Reed Richards from the F4, your plasticity amazes me- and that is a compliment.

I am thinking progressives need to formally respond to this Corporate Tax reduction. There needs to be a clear response to counter the claims being made.

I hope Andrew and his band of merry-people can make headway on such a paper.

It is truly needed in a big way.

Great summary here. On tax neutrality for debt financed investment I thought the idea was due to Stiglitz not Samuelson. As Samuelson once famously wrote “Joe Stiglitz is the best economist ever to come out of Gary, Indiana.”

Thanks. I believe the article was: Paul Samuelson, “Tax Deductibility of Economic Depreciation to Insure Invariant Valuations,†Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 72 (December 1964), pages 604-606.

Stiglitz was still a student then. However, it’s interesting that they were both from Gary.

Conversely, to the extent that the equity investor is:

a) A non-U.S. foreign corporation;

b) An individual Canadian investing through his or her RRSP; or

c) A Canadian pension fund;

then the argument does not go through. Note that in cases b) and c) there is no dividend tax credit.

Indeed. An honest advocate of Canadian corporate tax cuts would argue that they could be relevant to this subset of equity-financed investments. Instead, we are bombarded by misleading claims that corporate tax cuts will boost business investment in general.

It is worth noting that RRSPs and pension funds do not receive dividend tax credits because they do not pay personal tax on investment returns. But unlike the dividend tax credit, being exempt from personal income tax is not directly linked to the corporate income tax rate.

Even though exemption from personal tax lowers the hurdle for potential RRSP and pension investments, corporate taxes might still prevent some from getting over it. If this problem were serious, slashing corporate tax rates would not be the best solution. Just making the dividend tax credit refundable would be far cheaper.

rcp: Well, actually, on (a) it would have to be a non-US foreign corporation from somewhere with a corporate tax rate even lower than Canada’s, wouldn’t it? Anywhere else, the same logic as the US case would apply.

And outside of the Caiman islands or some such, there hardly is anywhere like that.

Purple Library Guy: agreed that the rate has to be lower than Canada’s to make a difference on (a). As the Canadian corporate tax cuts get phased in there are fewer jurisdictions where that’s true – that’s the point. We’ll end up with a combined federal/provincial corporate tax rate of about 25% in Ontario, for example.

But it’s not just the Cayman islands that has rates below 25%. The OECD has some corporate tax rates here.

The link looks misspelled but that’s their doing. Note that 25% is close to the average rate. I agree that there’s little point in pushing past a combined corporate rate of 25% or so.

I looked at that list. It’s true that in terms of numbers of countries 25% was around the middle of the pack. But the countries below 25% were almost all little Eastern European countries who aren’t gonna be doing a lot of investing in Canada anyway. That and Ireland, Iceland and Greece . . . well, Irish finance capital might do some investing in Canada, they sure won’t be investing in Ireland any time soon. The only countries worth worrying about losing investment from on the list would be Turkey and Switzerland.

In any case, Canada probably has too much foreign investment already.

That’s right. The OECD and global averages are 25% only because small tax havens drag down such unweighted averages. With countries appropriately weighted by GDP, Canada was already in line with OECD and global averages before our current round of corporate tax cuts.

Also, those OECD figures appear to be out of date. Iceland raised its corporate tax rate in 2010.

Erin, the OECD numbers that I cited do not include tax havens, although the global averages do, as I’m sure you know. And I’m not surprised that Iceland has raised the corporate tax rate, given their recent problems.

I agree, as I said, that taking the corporate tax rate below 25% does not seem necessary from a competitive point of view at this time. If the U.S. ever drops their corporate rate, it would make sense to re-examine the issue, but their huge deficits make that seem unlikely in the near future.

PLG, what is the basis for saying that there’s too much foreign investment in Canada?

the OECD numbers that I cited do not include tax havens

That is true if you accept the OECD’s definition of “tax haven.†(Strangely enough, it never applies this label to its own members.) However, a broader conception of the term would include Chile, Iceland, Ireland and some Eastern European countries.

The whole tax rate – hurdle argument is far to academic. There are so many subsidies available to large corporations that enter into the equation that the tax rate is only one factor that sets the hurdle. For some industries (like glass manufacturing) the tax rate would need to be negative to overcome the energy subsidies that offshore competition receives.

Thanks to you and to Andrew for excellent posts focusing on the after hurdle rate of return.

I have to admit I’d been somewhat perplexed by the paradox of declining corporate tax rates accompanied by declining rates of business investment. Even I imagine that there should be some positive impact, but instead it has appeared to have a perverse negative impact instead. When I was considering this a few years ago, I thought this could make sense is if corporate decisions are based not so much on profit maximizing, but on profit rate satisficing.

I’ve seen some of this in action with businesses looking for gov’t support during the early 1990s. In this way, unit or region execs are told they have to show at least an XX% after tax rate of return to satisfy their head offices. If they are able to achieve this the easy way, with reductions in their tax rates, then it saves them having to make productivity-enhancing investments. If this is the case then further cutting the CIT rate can have this perverse effect of actually leading to lower rates of business investment.

Of course, there are many other factors at play, including other costs, competitors, value of the dollar, etc., I don’t know whether anyone has looked into this but this relationship may be a factor for the many Canadian businesses & business units that are not particularly dynamic or aggressive.

I have been working with a data set on corporate profits and investment rates and can’t find any positive correlation btw the two. This too shocked me. The Link between profits and investment is pretty much accepted by all schools of thought. I think we error when we search for the link at the national level. In a world of mobile capital and thus a buffet of investment geographical investment options the link between national cit rates and and national investment rates is broken.

That was the point of neoliberalism cum globalization no?

Looks like that OECD average might be moving:

http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20110126/us_nm/us_obama_speech_tax

The idea is the old one of cutting the rate while broadening the base. That’s what I get for predicting that large deficits would put the issue out of bounds.

By contrast, Canada’s approach has been to slash the corporate tax rate without broadening the base.

Thanks Glen, Toby and Travis for injecting a dose of reality into the debate. I wrote about the hurdle rate of return not because I believe it accurately models how businesses actually make investment decisions, but because it seems to be the most compelling argument for corporate tax cuts.

“On all of those investments, corporate taxes were a perfectly efficient and costless source of public revenue.”

One could also say that on all final consumption that would have happened anyway despite consumption taxes, consumption taxes are a perfectly efficient and costless source of public revenue.

So the issue then becomes whether consumption is more “inelastic” with respect to tax rates than investment before one can conclude which is more “efficient”. And on that count consumption taxes are more efficient.

I might add that a cut in the corporate rate DOES increase the return on Canadian equity because it increases the size of the potential dividends.

“I wrote about the hurdle rate of return not because I believe it accurately models how businesses actually make investment decisions”

NPV modeling is the cornerstone of corporate finance so if you don’t believe that’s “how businesses actually make investment decisions” I presume you will be advising B-schools around the world to change their curriculums to teaching whatever the “real” decision tool is.