More Nonsensical Canada-Ireland Comparisons

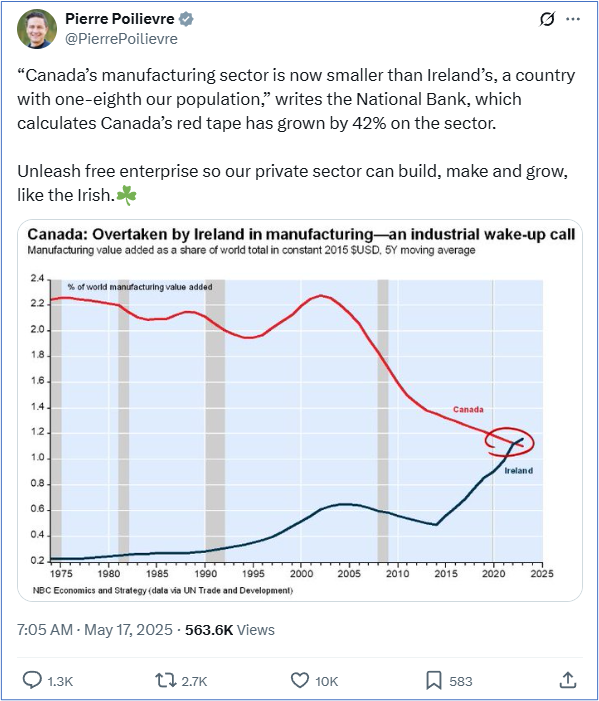

Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre recently circulated a post on several social media platforms claiming that Canada’s manufacturing industry has atrophied under excessive regulation and high energy prices to an extent “unmatched across the industrialized world.” It purported to show that Canada’s manufacturing sector is now smaller than Ireland’s—a country with one-eighth of Canada’s population. This, he argued, is due to stifling red tape, and he called for a “free enterprise” policy so we could catch up to the Irish.

Poilievre’s post was based on a one-page blog commentary from researchers at the National Bank, who claimed this shocking outcome is an “industrial wake-up call” for Canada to reduce regulation and cut energy prices.

The claim that Canada’s manufacturing sector is smaller than Ireland’s is false, and constitutes another clear misuse of comparative GDP statistics between Ireland and other industrial countries. Similar manipulations involve comparisons of other indicators like per capita GDP or productivity between Ireland and other industrial countries. I recently explored the problems of per capita GDP comparisons to Ireland in a commentary for Policy Options.

Ireland is a tax haven. It has the lowest corporate tax rate in the EU. This has incented major multinational corporations (like Apple, Microsoft, and Pfizer) to establish subsidiaries there. By using internal transfer pricing and other artificial arrangements to shift bottom-line profits to Ireland, they avoid paying higher tax rates in other countries. This is good for those companies, but undermines government fiscal capacity in all countries.

This practice also artificially boosts Ireland’s reported GDP, since profits of an Irish-based subsidiary count as domestic value-added. (They are not counted in gross national product, which measures the value-added owned by Irish people; GNP is about one-third lower than GDP in Ireland’s case, an unusually large gap between the two measures that reflects the distorting effect of MNC profits there.) Foreign-dominated sectors make up about 45% of Ireland’s GDP, and most of that consists of corporate profit—very little of which is ever touched by Irish people.

This artificial inflation of Irish GDP statistics is especially severe in Ireland’s manufacturing sector, since most of those multinational firms using Ireland as a ta-avoiding base of operations are defined as manufacturers (mostly in computers, other technology, and pharmaceuticals). Compared to inflated value-added statistics, surprisingly little of their tangible industrial output is actually produced in Ireland.

According to Irish statistics, about 75% of manufacturing value-added is concentrated in computer and electronic equipment and pharmaceuticals. The large majority of that value-added reflects profits captured by overseas multinationals, with little relationship to the output, incomes, or well-being of Irish people.

This tax avoidance badly distorts statistics on economic activity of various sectors in Ireland. Manufacturing accounts for 31% of Irish GDP, but only about 10% of employment—much of which is employment in the offices of those Irish subsidiaries (as opposed to people actually making stuff). Yes, manufacturing has higher average productivity—but that cannot explain a 3-to-1 difference between the GDP share and the employment share.

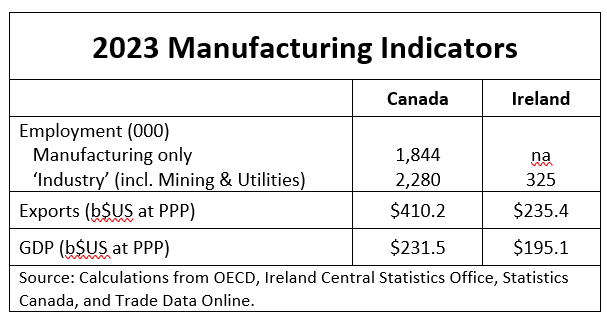

Ireland’s labour market data reports employment for a broad category called ‘Industry’ (which includes manufacturing, mining, and utilities). That broad sector employed 325,000 people in 2023. In Canada, manufacturing proper employed over 1.8 million people that year. Including mining and utilities (to be comparable to Ireland’s ‘Industry’ category), Canada employed close to 2.3 million people. Canada’s manufacturing sector thus employs 6 to 7 times as many people as Ireland’s. It is ridiculous to claim that Ireland’s manufacturing sector is ‘bigger’ in any material sense.

Another measure less sensitive to the distorting effects of Ireland’s GDP statistics is exports, which measure flows of actual merchandise (rather than paper transactions). Ireland exported about 180 billion euros worth of manufactures (broadly defined to include crude materials and fuels) in 2023. That is about $235 billion (U.S.) at the OECCD’s purchasing power parity exchange rate for that year. Canada exported $465 billion worth of (more narrowly defined) manufactures that same year, or $410 billion in $U.S. dollar terms (at the PPP exchange rate). That is 75% more than Ireland. And since Canada is much larger than Ireland (by both geography and population), exports constitute a smaller share of total manufacturing output here. Hence the ratio of physical manufacturing output will be higher still for Canada—almost certainly twice as large.

Even by GDP comparisons, distorted by the paper-profit-shifting problem discussed above, Canada’s manufacturing output is about 20% higher than Ireland’s (compared at PPP exchange rates). Keeping in mind that over half of Ireland’s supposed manufacturing value-added reflects the artificial profits of multinational firms, it is clear that by any measure Canada’s manufacturing activity is much larger than Ireland’s.

The claim by both Mr. Poilievre and the National Bank that Canada’s manufacturing sector has suffered a catastrophic decline is also false. The National Bank chart reposted by Mr. Poilievre describes a very unusual metric: it shows each country’s share of world manufacturing GDP, valued in 2015 constant-dollar terms, converted to $US at the 2015 exchange rate, and then transformed again to a 5-year moving average. In addition to the fundamental problem of accurately measuring Irish GDP, therefore, this metric embodies four additional transformations of the data—each of which creates opportunity for misunderstanding or even manipulation:

- Thanks to the rise of China and other emerging manufacturers, virtually every industrial country’s share of world manufacturing output has declined over this period (Ireland is an exception due to its distorted GDP statistics).

- The choice of 2015 constant dollar GDP overstates the apparent value of industries with rapid technological change (especially computers, which are a large share of Ireland’s manufacturing).

- That choice also freezes in time the 2015 exchange rate, which can also distort relative values (Canada’s currency was weak in 2015, following the previous year’s oil price crash).

- The use of 5-year moving average is very suspect: it creates a nice smooth line, but can lead to very erroneous conclusions.

On this latter point, consider that official Irish data indicate that real manufacturing GDP collapsed by 23% in 2023. Why? Because most of that supposed GDP consists of the profits of multinational firms, which reached all-time highs in 2022 (thanks to profit-led inflation following the COVID pandemic). As supply chains normalized, profits around the world fell in 2023. In Ireland’s case, that caused a sharp decline in apparent GDP—but with little impact on actual work and output.

Honestly portraying this extreme volatility of Irish manufacturing GDP would raise immediate suspicions about what these statistics actually portray. How could a supposed industrial success story be prone to such extreme roller-coasters of activity? And how could industry contract 23% in one year without widespread hardship and factory closures? This bizarre feature of Ireland’s GDP statistics is hidden, however, by the arbitrary use of a five-year average. That 23% decline in output in 2023 (the last year of the National Bank chart) would have left Ireland’s line—even with its misleading conception of GDP—well below Canada’s. That would have spoiled a great sound bite (and no doubt mitigated against the chart’s use as a Conservative talking point).

The National Bank’s CEO, Laurent Ferreira, is celebrated in conservative media and political circles for his strong critiques of Canada’s “excessive regulation and oversight”, and for opposing an emissions cap on the petroleum industry. The National Bank’s strangely convoluted and misleading blog post is fully aligned with Ferreira’s perspective, even down to stressing the importance of deregulation and expanded energy supply for future manufacturing success. The vigour with which this research was taken up by the Conservatives’ communications team further indicates close alignment with right-wing talking points.

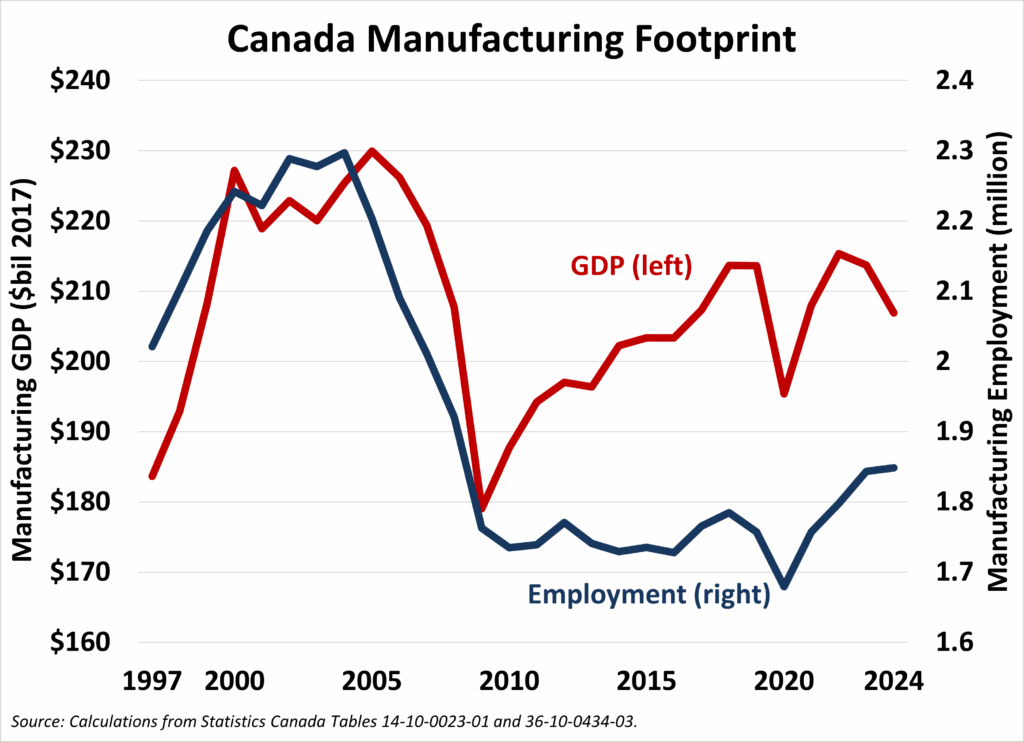

The post’s claim that the “profound atrophy of Canada’s manufacturing base [is] unmatched across the industrialized world” is not remotely true. Yes, manufacturing in Canada has experienced many challenges since the turn of the century. The sector experienced a sharp decline in both GDP and employment from 2005 through 2010 (most of which occurred under the Conservative government of Stephen Harper). This downturn reflected the negative spillovers of an overvalued currency (largely caused by rapid expansion of petroleum exports, which Mr. Ferreira wants more of) followed by the 2008-09 financial crisis (including a near-meltdown in the automotive industry).

However, the industry stabilized after 2010. It has since won back about two-thirds of the GDP lost during the latter 2000s. Employment has increased, but more modestly. (The fact that GDP has recovered faster than employment reflects productivity growth in manufacturing, which is also a good sign.)

In short, the hard data on Canadian manufacturing does not at all confirm to the “lost decade” narrative of Mr. Poilievre and his supporters. If anything, it shows manufacturing still recovering from a much earlier crisis in the late 2000s, when policy neglect and a dollar above par dealt a body blow to domestic industry. Canadian manufacturers are challenged, but resilient. This is a more genuine depiction of the state of Canadian manufacturing, than the convoluted National Bank chart, which deliberately conveys a false impression of continuous decline.

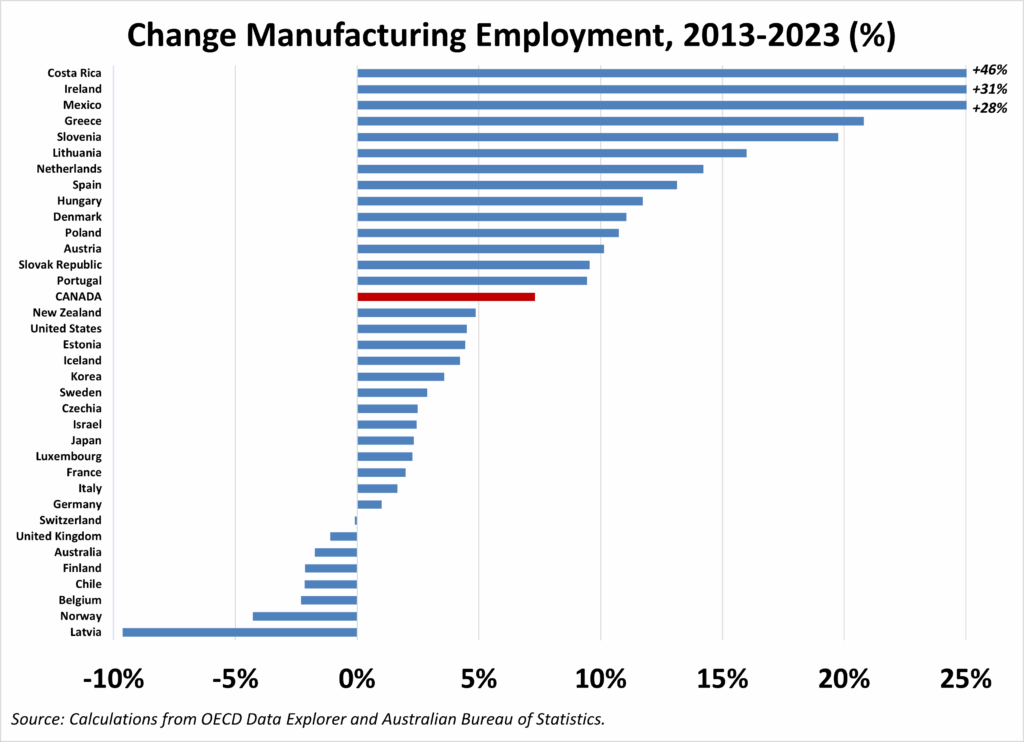

And in international terms, the claim Canada’s industrial decline is “unmatched” is an outright lie. Most industrial countries face similar challenges of deindustrialization, the rise of emerging exporters, energy transitions, and other factors. Canada ranks in the middle of the OECD pack. For example, according to OECD data, manufacturing employment in Canada grew 7.3% in the decade ending in 2023—slightly better than the OECD average, and better than the U.S.. We ranked 15th among 36 OECD countries reporting data by that score.

Yes, Ireland’s manufacturing employment grew very rapidly: by 31% over the same period (second only to Costa Rica in the OECD). If we had more detailed data (disaggregating production workers from office workers, for example), it would likely confirm that most of those jobs are not in factories, but in the offices of Irish subsidiaries of global firms (which are classified as manufacturers). Most of them are working on tax loopholes, not tangible products.

Conservative commentators have tried to use Ireland as a poster child for free market economics for years. Their empirical claims are flawed, and belie a deep misunderstanding of how Ireland’s economy works. Mimicking Ireland’s recipe, as Mr. Poilievre suggests, would involve trying to make Canada a tax haven. This wouldn’t work, even if we were convinced it was a good thing. There are good reason tax havens are always small countries, usually islands: to concentrate the lure of the tax incentive on mobile companies and investors, and then share the resulting largesse amongst a relatively small host population. Canada wouldn’t work as a tax haven, and most Canadians don’t want to try. Much better to work with other countries on international tax rules to limit the mis-use of policies like Ireland’s.

Ireland is not the richest country in the OECD on per capita grounds. It does not have the highest productivity growth of any country on earth. And it does not have a larger manufacturing industry than Canada. What it has is a tax regime that is immensely lucrative for global companies and the billionaires who run them—but that delivers scant benefit to most Irish people, and undermines fairness and economic efficiency everywhere else. Including Canada. Mr. Poilievre’s mis-use of this blatantly misleading factoid reveals both his pro-business biases, and his communications team’s failure to fact-check their economics.