Who’s Afraid of Deficits?

We all knew that Budget 2015 was optimistic about medium term growth and rebounding oil prices, but the good people at the PBO have given us an indication of just how far off those projections were. They estimate that nominal GDP will be about $20B lower through 2020 ($30B lower in 2016), which also means bigger government deficits through 2020.

While pundits had been OK with small, temporary deficits, at this news some headlines shouted that the Liberal’s plan to balance the budget was in jeopardy, and others contemplated the possibility that the new government would be less bold in the face of economic weakness.

Of course that is exactly the wrong response, and gladly McCallum pointed out the obvious, that this news “is something that underlines the need for the job-creating infrastructure investments”.

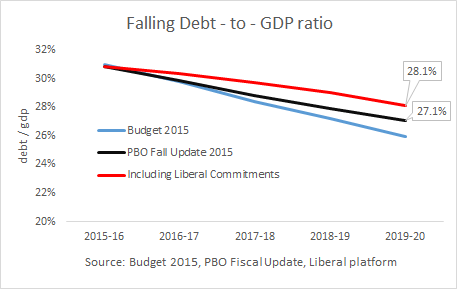

There has emerged a mainstream consensus that deficits / surpluses don’t matter so much, that a better yardstick of fiscal sustainability is our debt-to-GDP ratio. So what does yesterday’s news mean for this indicator?

Assuming the Liberal government fully implements the investment promises in its platform and the PBO projections are correct, the debt-to-gdp ratio is still projected to fall by 3 percentage points between now and 2019/20. In fact, the ‘modest’ deficits proposed in the Liberal platform only add 1 percentage point to the debt-to-GDP ratio over this timeframe, which translates into an increase of about $42B in debt between 2015/16 and 2019/20. (And, all of this assumes that there is no short term stimulative effect from the proposed spending either.)

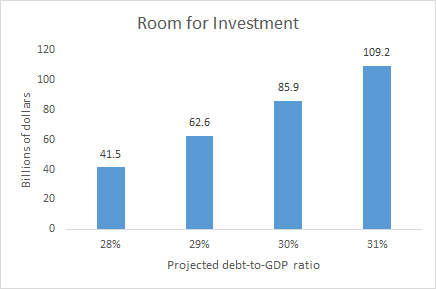

Let us look at the increase in spending/borrowing over the 2015-16 to 2019-20 timeframe that would result from targeting various debt-to-gdp ratios.

Assuming the PBO projections for GDP growth are correct, the federal government could borrow more than twice as much over the next four years – $86B – and the debt-to-GDP ratio would still be lower than when they took office.

Given that the economic news has worsened, a case should be made for increasing spending. Even though we aren’t in a recession any more, we are facing a period of what Armine calls “slowth”. Demographic shifts, among other things, are limiting our economic potential. Investments should target medium to long term growth, and meet basic needs that have fallen through neo-liberal cracks – such as clean water for First Nations communities.

There is more than enough room for increased investment, even given mainstream economic constraints.

Re: “There has emerged a mainstream consensus that deficits / surpluses don’t matter so much, that a better yardstick of fiscal sustainability is our debt-to-GDP ratio.”

As John Kenneth Galbraith has quipped, “In economics, the majority is always wrong.”

In Canada, the public debt ratio is an irrelevant focus of attention.

Crikey, why is it is honourable to deliberately increase unemployment?

Australian economist William Mitchell

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=30105

The public debt level relative to GDP is not a matter of economic concern ever if the government in question issues its own currency and only issues debt in that currency.

Under those circumstances the government can always service its nominal liabilities and the public debt ratio is an irrelevant focus of attention.

At any time of its choosing, the government could cease to issue public debt and continue deficit spending at will. It might have to change some regulations and statutes which have been put in place to give the impression that the debt issuance is funding its net spending, but that would be merely legislative activity.

Remember the government just borrows back what it spent in deficit in a previous period. Bond sales draw on private saving which is just a reflection of past deficits.

The utterly depressing thing that I was trying to communicate was that the mainstream response should have been “oh, I guess we’ll have to borrow slightly more to maintain counter-cyclical spending”, and instead it was “OH, NO, we can’t afford the Liberal platform promises!”.

Given where the econony has been and may be heading, still no sign of any major turn around- it may be a moot point soon that deficits much larger than projected will be required.

Two pillars of the economy:

traditional productive economy- manufacturing and resource extraction are both still in decline.

financialized economy- housing bubble is coming apart – and will impact consumption and credit markets for families who have relied on liquidity drawn down of asset appreciation over the past 10 years. This will also have a large impact on banks, finance sector and the profits derivied from the highly leveraged trading in various derivatives. Which means govt may well need to bail out said banks that are over exposed to risky mortgages and the asset backed securities attached. This also have a direct impact on construction sector- which has long played a mitigating role to the decline in manufacturing in many large regional economies.

All this to say- soon we will not to worry too much about this debate on affordibility of deficit. This assumes of course that the Banks come out of the backroom dealings and their special relationship with CMHC. We all recall the great recession and the lack of tranparency in the asset back security write downs that were caused by exposure to the US housing sector of Canadian banks. Not a lot of transparency back then. At least the US banks when they were handed 4 trillion from the Fed balance sheet to buy up those mortgages- acknowledge it!

Trudeau’s infrastructure plan is a decent one, and will have clear long-run benefits, and medium-term effects in bolstering aggregate demand. What we really need is heavy stimulus right away. Given federal constitutional arrangements, many of the tools for quick stimulus are at the disposal of the provinces. What I recommend is that the GC, as a first step, just upload 50% or 60% of provincial and municipal debt. As Larry Kazdan and others often point out here, the GC is not limited fiscally in the same way as provinces, and such a measure would:

1) Undermine provincial austerity measures;

2) Allow for much needed tax cuts and investment;

3) Avoid any constitutional squabbles;

4) Support the federalist cause at the provincial governement level in QC;

5) Be possible now more than at any time, because certain traditional “have” provinces need more support than they have in over a generation, and so their governments will not oppose such a measure.

In Wacky Bennett’s words, “nothing for nothing, though.” So one might wish to tie in one or two clauses around national standards, in healthcare, the environment and education, and provincial tax cuts, but that is not essential, merely highly preferable.

Since much of provincial debt has arisen because of a lack of federal spending over the last 2 1/2 decades (especially a lack of federal countercyclical spending), the Government of Canada would, effectively, just be making up for its past errors. Give ’em tax cuts, and Canadian electors will eat it up.

I too was brought up short by the “a mainstream consensus has emerged” paragraph, because it sounds like perhaps you wouldn’t go that far (which isn’t the case as you say). It just needs a little extra like “Even mainstream economists have at least been able to come around to a consensus that deficits and surpluses are irrelevant and now use debt-to-GDP ratios as their fiscal sustainability yardstick.” I think that lets you introduce the debt-to-GDP calculations without having to accept it as the limit (or appearing to prefer deficit/surplus thinking). By the way, I’m not sure a “mainstream consensus” has emerged–I think it’s just a consensus among mainstream economists. The punditocracy seems willing to accept tiny deficits, but looks to be a long way from any awareness of actual debt-to-GDP ratios.

You’re correct, I was referring to mainstream economists.

See this, from The Economist: http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2015/11/what-britain-forgets?fsrc=scn/tw_ec/why_running_a_budget_deficit_can_reduce_the_national_debt

And the PM’s direction to the Finance Minister included: “continuing to reduce the federal debt-to-GDP ratio throughout our mandate.” http://pm.gc.ca/eng/minister-finance-mandate-letter

Progressives should know that there’s lots of room to push for increased investments, even within that limited mandate.

Canadian pundits are going to become far more familiar with this concept, I’m sure.

I’m fascinated that many blog entries here continue to focus on irrelevant financial concerns instead of full employment. The Canadian government is not financially constrained in absolute or relative terms and can never go bankrupt. It doesn’t get more categorical than that. Why then engage with the flat earthers on a useless discussion about fiscal sustainability when our energy should be directed at making the case for chock full employment? Functional finance trumps sound finance.

While the federal government can’t go bankrupt, the value of the dollar can collapse which is equivalent to bankruptcy, especially from the lender’s point of view.

Implementing a guaranteed annual income would be a better and simpler approach then going for full employment. Eventually automation can eliminate most work. That should be our long term goal.

When you say the value of the dollar can collapse I’m guessing you mean via inflation? It’s true that inflation can result when spending outstrips the economy’s real resource capacity, but there’s nothing special about government spending. Spending is spending and the cash register doesn’t care where the money comes from.

I respectfully disagree that a guaranteed income is preferable to a guaranteed job. Even if most routine work could be eliminated with automation, there will never be a lack of meaningful work to do nor should there. There’s dignity in earning your daily bread that can never be replaced by a grant or handout. I don’t know about you, but I want nothing to do with a WALL-E world.

Realistically, it’s not an either-or for full employment or guaranteed basic income. Consider the dignity of everyone having the opportunity to work, but just 25 hours per week instead of 35 or 40. More time for parents to spend with their children, etc. And then of course there are the seasonal careers. I live on PEI where all three of the major industries – farming, fishing, and tourism – basically disappear for 3-6 months every year. But the farmers and fishers that I’ve met certainly don’t lack for dignity in their hard work.