Fiscal and Economic Record of Political Parties

A version of this originally appeared in rabble.

Conservative ads have focused on the NDP’s fiscal and economic record, claiming that the “NDP Can’t Manage Moneyâ€. These include another round of staged interviews with people who repeat “the NDP can’t manage moneyâ€, “the cost of their plans is hugeâ€, that “business will be under attackâ€, they’ll be “reckless spenders†and “my family can’t afford the NDP.â€

These lines feed into a central Canadian and media stereotype of NDP governments as reckless spenders and taxers. Meanwhile early polls reported that Canadians trust Tom Mulcair and the NDP more than any political leader and party when it comes to economic issues. Who’s right on this issue?

I examined the records of all provincial and federal governments from as far back as consistent data are readily available (1981) against relevant major fiscal and economic indicators. The results may be quite surprising. NDP governments have been far more “fiscally responsible†overall than either Conservative or Liberal governments. They also rank on top for a number of other key economic indicators, including lowest unemployment rates, highest real wage growth, and–surprisingly–highest growth in corporate profits.

For instance, on key fiscal measures:

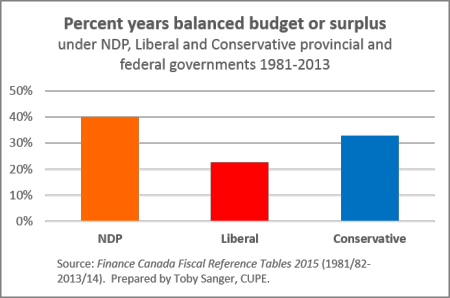

- NDP governments have balanced their budgets 40% (or 22 of the 55) years they’ve been in office, compared to just 33% for Conservatives and 23% for Liberal governments.

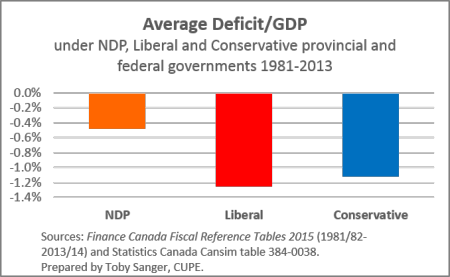

- Deficits under NDP governments have averaged 0.5% of GDP compared to 1.1% for Conservative governments and 1.3% for Liberals.

- Average debt-to-GDP ratios are similar for NDP and Conservative governments at 24%, lower than the average under Liberal governments at 35%, but Conservative governments have increased debt/GDP ratios at a higher rate than either Liberal or NDP governments.

- Far from being big spenders, NDP governments have actually averaged slightly lower spending as a share of their economies than either Liberal or Conservative governments at 21.6% compared to 22.2% for Conservative and 24.6% for Liberal governments.

- NDP governments have also not been big taxers: their revenues as a share of their economies have averaged 21%, similar to Conservatives and lower than the average under Liberal governments at 23.4%.

The long reign of Conservative governments in Alberta significantly improved their averages, just as the NDP’s short recessionary period in office in Ontario worsened theirs. If these two provinces are excluded, Conservative governments fare considerably worse and the NDP fare even better.

When only provincial governments are considered, NDP governments still average lower deficits, lower increases in debt/GDP and lower spending and revenue ratios than either Liberal or Conservative governments. Conservative provincial governments have averaged the lowest debt/GDP ratios, but that’s entirely due to Alberta. When only federal governments are considered, Conservative governments have had worse fiscal records since 1981, with higher average deficits and larger increases to debt than Liberal governments.

Despite their lower rates of government spending, NDP governments have also tended to have good results when it comes to other economic indicators.

Unemployment rates have averaged 7% under NDP governments compared to an average of 9.7% under Conservative governments and 10.8% under Liberal governments. This is in part because of the NDP’s relatively longer periods in office in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. But when individual provinces are considered—unemployment rates have also tended to be lower under NDP governments, including in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia—but higher than Liberals in BC and also higher than other governments in Ontario.

Real average wage growth has also been stronger under NDP governments, averaging 0.89% annually after inflation compared to 0.66% under Conservative governments and under 0.63% under Liberal governments. Once again, overall Conservative averages are significantly improved by their long period in government in Alberta. If that province is excluded, workers’ wages have grown at a slower rate under Conservatives than under either Liberal or NDP governments.

Real GDP and job growth has been slightly higher under Conservative governments, but those again are legacies of the long period of Conservative governments in Alberta and the NDP’s recessionary term in Ontario. If those two provinces are excluded, annual job growth has averaged the same under all major parties at 1.1% annually and average real GDP growth has been very similar: 2.2% under Conservative governments and 2.3% under Liberal and NDP governments.

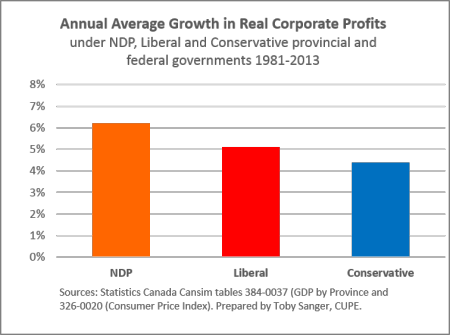

What may be most surprising is that average corporate profits have also grown at a faster pace under NDP governments than under Liberals or Conservatives. They’ve increased at an average rate of 8.7% annually under NDP governments compared to 7.8% under Conservatives and 7.6% under Liberals. When inflation is taken into account, corporate profit growth has still been highest NDP governments at 6.2% highest, second highest under Liberal governments at 5.1% and lowest under Conservative governments at 4.4%. When considered by individual province, profit growth has been strongest under NDP governments in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and BC, and second strongest in Ontario under the NDP.

Economic and fiscal indicators for political parties by province can be strongly influenced by general economic conditions and so were worse for the NDP in Nova Scotia and Ontario as they were in power in those provinces for just one term during recessions and their immediate aftermath.

However, when considered overall, the three major parties have been in office during expansionary periods for a remarkably similar share of their total time in office: 61% in the case of Liberal and Conservative governments and 62% for NDP governments. Accordingly, most of these results are very similar in terms of relative rankings when recessionary and immediate recovery periods are excluded.

There are of course differences by province, time period, particular administrations and economic cycles, but overall these results show that far from being “reckless spenders†and bad managers of the economy, NDP governments have been the opposite: very fiscally responsible and rank as the top managers of public finances and the economy on most significant indicators.

This may be at odds with the media stereotype of NDP governments in central Canada, which is heavily influenced by the business press as well as by the NDP’s brief tenure in power during Ontario’s deep recession of the early 1990s. But this tradition of fiscal responsibility and strong economic management is very consistent with the NDP’s origins and history in western Canada.

The NDP’s traditional of fiscal responsibility has deep roots, as David McGrane has written, back to the predecessors of the NDP. The first thing Tommy Douglas, CCF Premier of Saskatchewan and the first leader of the federal NDP, did after he became Premier in 1944 was balance the budget, including by raising taxes on business. While his government introduced numerous innovative reforms in their first term in office, it took many years until his government was able to introduce Canada’s first public health care system.

Douglas never ran a deficit during his 17 years as Premier of Saskatchewan and dedicated 10 per cent of provincial revenue to paying down the provincial government’s debt, built up during the war and from years of Liberal mismanagement. Douglas and his social democratic predecessors—and successors—didn’t want to be indebted to bankers or at the mercy of financial markets. As we’ve seen with the fate of social democratic governments in Greece and elsewhere, they had good reason to be wary.

NDP leader Tom Mulcair has been criticized for pledging that an NDP government would balance the federal budget in the first year if elected by a number of economists who have argued balancing the budget will lead to continued stagnation and that we need more economic stimulus through government spending and investment.

This is a valid point, but NDP governments tend to be held to higher fiscal standards than other governments of different political stripes, as Marc Lavoie has observed. While Conservative and Liberal governments, with their closer ties to the financial sector, have often been re-elected after running large and persistent deficits, NDP governments that have done so have  been heavily criticized and defeated in subsequent elections. It’s similar to the “Nixon going to China†phenomena. It was acceptable for a Republican to be the first American president to go to China, but if a president from the Democratic party had done so, they would have been seen as cozying up to the communists.

While deficit spending can help stimulate a struggling economy the composition and type of public spending or taxation is just as important or more important than its overall level.  John Maynard Keynes may have sardonically suggested the government could stimulate the economy and eliminate unemployment by burying old bottles with banknotes in disused coal mines “and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up againâ€, but he followed that by saying “It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.â€

Every dollar invested in education, health care and other public services generate five times as much employment and economic growth as a dollar in corporate tax cuts. In fact a balanced budget that has the right policy mix of expenditures and taxes can provide a stronger economic boost than a deficit budget with the wrong policy mix, such as corporate tax cuts which get socked away or channeled into speculation. Conservative and Liberal governments have applied failed trickle-down economic policies for decades that have not only increased inequality, but have also led to meagre and declining economic growth. They’ve also too frequently used the public purse to enrich their wealthy friends instead of being responsible guardians of public finances. And despite what neoconservatives may claim, higher wages for workers and greater equality are good for the economy.

NDP governments might not appoint Bay Street bankers as their Finance Ministers or be beholden to them, but they’ve delivered better economic results to Main Street—and that’s what should matter.

——————————————————–

Sources and methods:

Data sources include:

- Finance Canada Fiscal Reference Tables 2015 for fiscal indicators from 1981 to 2013.

- Statistics Canada Cansim Tables 384-0037, 384-0038, 384-0039 and 384-0040 (GDP by province, available 1981-2013) 282-0087 (Labour Force Survey), 326-0020 (Consumer Price Index).

Fiscal year data was attributed to the initial calendar year, as quarterly data were not available for the major economic indicators by province.

Political parties were considered to be in office for that year if they were in office for more than six months of the calendar year, i.e. beyond the end of June. Because it can take time for policies to have an impact, analysis was also done applying the year in office to whatever party was in office at the very beginning of the year, but this made no significant material difference to the results.

The government of Canada owns a central bank that issues a sovereign currency. Canada’s fiscal capacity is not that of a province like Saskatchewan, nor a country like Greece that does not control its domestic money, the Euro. For a currency issuer, the targeting of balanced budgets under so-called normal circumstances is just a neo-liberal construct designed to restrict the influence of government, and to keep labour docile through high unemployment. Why is the NDP reinforcing this pernicious right-wing doctrine at a time when 1.3 million Canadians are without work? Long-term joblessness increases the rates of family breakdown, increases crime rates, increases alcohol and substance abuse, increases suicide rates, increases incidence of mental and physical problems, and results in lost opportunities for skill development and work experience among the young. The goal of the federal government should not be to balance the budget, but to use the budget as a tool to achieve public purpose which must include the opportunity for its citizens to earn income and contribute to society.

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=31487

“Austerity is about the spending position of the economic

system as a whole. The economy is either subject to a spending

gap – where total spending is insufficient to absorb the available

productive capacity – or it is not.

So when we worry about austerity it is because policy choices

are deliberately forcing the economy to operate at below

potential and mass unemployment is one of the consequences of that policy failure.

Accordingly, when there is a spending gap, the fiscal deficit

is too small, given the spending decisions of the non-government

sector.

There needs to be more net public spending.

So, discussions about taxing the rich or the corporations to

get “money†to match government spending in these cases is

rather missing the point.

There is no shortage of ‘money’ per se for a currency-issuing

government. One should never tie the spending capacity of such a

government to whether some cohort can ‘afford’ to pay more tax.â€