Banks and Balanced Budgets

The Bank of Canada surprised most analysts this week when it decided to cut rates by 25 basis points. The move comes after the price of oil has tumbled below $50 / barrel, oil producers announced huge cuts to business investment for 2015, Target announced a mass layoff of 17,600 workers in Canada, and the International Monetary Fund warned of a global economic slowdown.

The key message of the January Monetary Policy is that the Canadian economy needs stimulus. The Bank’s view of the Canadian economy stands in sharp contrast to that of the federal government, which is intent on delivering a balanced budget with a basket full of family tax cut goodies. By spending their surplus before they had even secured it, and then also sticking to an unrealistic balanced budget timeline, this government painted themselves into a corner, and made themselves look very foolish.

Thank goodness that the Bank was willing to act, and put the wellbeing of Canadians over concerns of a housing bubble and excess household debt.

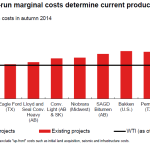

So, what was the biggest outcome of the announcement? The loonie fell to 81 cents USD, down nearly two cents on the day. It is now five cents lower than it was on January 1st. Since oil and other commodities are priced in US dollars, the lower loonie effectively boosts prices for Canadian commodities producers. For those that were operating at or just below their short-run cost margins, this is great news. According to the following chart taken from Timothy Lane’s remarks on January 13th, that includes several sites in Canada.

While many analysts pointed to how this move was good for manufacturing, the most immediate impact of the Bank’s rate cut is to save thousands of jobs in the oil, gas, and mining sector.

As I’ve pointed out before, the benefit to manufacturing depends partly on the ability of existing manufacturing firms to grow. New entrants will be unlikely to rely on the lower dollar to stick around forever, but may be able to use the current cushion to get their projects off the ground. This will take some time. The lower dollar increases most machine and equipment input costs, so labour intensive firms actually have the advantage in the current environment.

The Bank issues its next rate announcement in March, and many observers are considering the possibility of another rate cut at that time. What is that likely to depend on? Well, the Bank based their estimate on $60 oil, and it’s currently below $50. The price is unlikely to rise until something gives on the supply side. Canadian and American producers are currently saying that their production will increase this year, just at a slower rate than last year. Saudi Arabia seems intent on keeping supply high until it forces some of those North American producers out of the market. If the price of oil stays low for the next couple of months, we could easily be looking at yet another cut from the Bank. Would it be enough for Stephen Harper to give up on a balanced budget? That’s a tougher question.

How deep will the Canadian recession be?

A simple way of looking (an in fact perhaps painfully obvious) at things is that the burst commodities bubble (not only oil but iron ore, coal and potentially others) is likely to have the same scale of effect on the Canadian economy as the burst high-tech bubble did in the U.S. in 2001 which is recession. In some ways the effect could be larger in Canada given the importance of commodities to the Canadian economy relative to the importance of the high-tech sector to the U.S. However there are three important differences from the US experience in 2001 both of which are on the negative side. First, because of the low interest-rate environment and the pressure on firms to engineer higher Earnings per share growth, my guess is that a lot more debt w ahs been involved in financing the commodities boom in Canada than was in in the U.S. high-tech boom (proportionately-speaking. A second is that in 2001 the Federal Reserve cut interest rates dramatically (something which was probably an important factor contributing to the subsequent U.S. housing boom/bubble). The U.S. housing sector had been in a boom since the mid-1990s but the boom/bubble still had 4-5 years to run in 2001. The BOC has very limited scope for manoeuver given the low interest rates; ii) Canada is in a very late stage of a housing boom (I would argue bubble) but even if one assumes housing boom, there are significant risks that a recession will knock over the housing market given the high level of leverage that have been associated with the boom. If a major housing slump were added to a commodities bust-induced recession, this spells deep recession. So no wonder the BOC is acting decisively cutting interest rates (to get a normal (if the interest rate environment can at all be described of as normal) upward-sloping yield curve; and probably preparing for possible QE. Given the options open to them they are pursuing the best course of action open to them. That is why the foreign exchange market reacted so strongly to the BOC action. However the plunging five-year government bond rates are another strong market sign of recession, to which the foreign exchange markets have been reacting. I have always thought that in this ongoing global economic crisis commodity-producing countries will fare very badly, if history is any guide. Perhaps we are seeing the first sign of the descent of the formerly high-flying (at least in relative terms) Canadian economy.

Oh, the wonders of helicopter money being dropped onto the heads of wealthy bankers. The finest in trickle-down economic theory.

We’re only 7 years into the slump, so things can turn around any minute now. (Actually I would say we’re more like 15 years in. GDP growth collapsed in the 2000s after the dot com bubble burst despite the new-and-improved housing/derivatives bubble that replaced it. Pre-post-war era boom-to-bust business cycles were resurrected after heavy-handed 2% inflation targeting was put in place: or what economic scientists call “The Great Moderation.”)

In any case, one has to wonder how many years (decades?) it will take before New Classical and New Keynesian economists stop patting themselves on the back and take a look at the mess they made? (My guess: the answer can be summed up in an equation whose dependent variable approaches infinity.)