Neoliberalism in Canada: 3 moments, 3 indicators

The current edition of Canadian Dimension magazine has a fascinating series of articles on episodes of economic transition around the world (more of them bad than good in recent times, of course). It’s a very thoughtful & informative collection, and I highly recommend it (and every progressive economist should subscribe to CD, by the way).

I wrote the article on Canada, reviewing the history of how neoliberalism was implemented here, and discussing some of its unique Canadian features (especially, of course, the unique role of resource extraction in Canada’s neoliberal economy). Here is the link to the full article in CD.

Many people think “in threes”: that is, when they are formulating an argument they include three main points, sections, or pieces of evidence. My friend and office-mate Frank Stilwell here in Sydney does that all the time, and famously (or infamously) so did my friend and former colleague David Robertson at CAW (so much so that we’d all tease him if he stopped any list after only two items!). I was obviously thinking “in threes” when I wrote this.

First I identified three main turning points marking the key moments of neoliberal structural change in Canada’s trajectory. These are the key changes that led the evolution of the firmly business-dominated, resource-dependent, and precariously unequal society we confront today:

1. The advent of high interest rates and abandonment of full employment as the central goal of macroeconomic policy. The sea-change in monetary policy is a common early historical feature of neoliberalism pretty well everywhere, and Canada is no exception. We were slightly late to the party: monetarism (and its more sophisticated descendants, culminating in the present inflation targeting regime) started here in 1981-82 … three years after the Volcker shock kicked it off globally.

2. The implementation of the Canada-U.S. free trade agreement in 1989 (followed, 5 years later, by Mexico’s inclusion into the free trade NAFTA zone). Apart from its direct and increasingly negative impacts on Canada’s economy, NAFTA has played a terrible role as a “template” for a whole new generation of free trade deals around the world (which are now routinely designed using NAFTA as the cookie-cutter, investor-state dispute settlement and all).

3. The acceleration of resource exports (especially petroleum) beginning around 2002. This resource-driven restructuring of Canada’s sectoral make-up has had enormous implications: for trade, for federalism, for labour markets, for inequality, for the environment. It occurred on the foundation laid by the FTA: including its still-unprecedented proportional energy sharing clause (that not even Mexico dared to accept).

It is interesting to note that only one of these three moments coincided with a political decision in Canada’s democratic process (the FTA, which was only confirmed after the Tories won the famous 1988 free-trade election … and even that was not exactly a democratic mandate, given the vagaries of our first-past-the-post voting system). The other two (neoliberal monetary policy, and the renewed reliance on resource exports) occurred with no direct democratic mandate. That also says something about how the world works today.

Then, continuing with my “threes,” I chose three summary empirical indicators of Canada’s economic trajectory, that I think well describe the varied impacts of neoliberalism here.

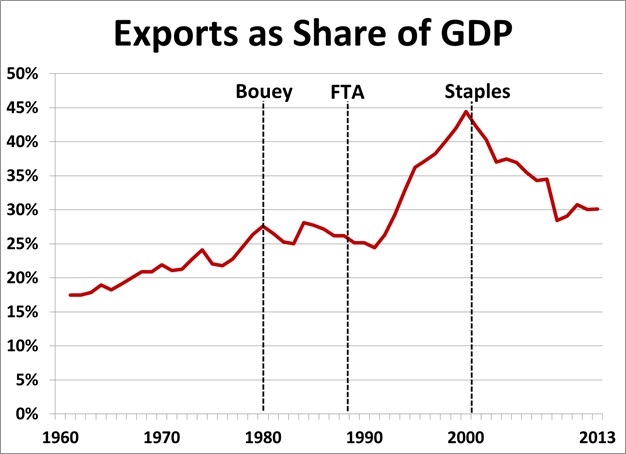

1. The overall importance of exports in GDP. (Caution: Erin Weir and others have noted this is a misleading indicator of trade-intensity, since it does not adjust for the import content of exports; but it is nevertheless a handy aggregate indicator of trends in trade-intensity over time.) This measure stagnated during the tight-money 1980s, grew dramatically after the FTA (as expected), then counter-intuitively began to decline with the advent of the petro-era. Gross export intensity, perversely, is now not much higher than when the FTA was being negotiated. This certainly gives the lie to the assumption that “globalization” is all about “trade.” In fact, globalization (as incarnated in NAFTA-like trade deals, anyway) is about something very different.

2. Aggregate productivity in the business sector, measured in real outpupt per hour of work, relative to the U.S. This is a shocking graph, first published by Andrew Sharpe’s Centre for the Study of Living Standards (see his Table 6 here). International comparisons of productivity levels are rare (due to methodological difficulties in comparing value-added across currencies, and other data challenges). Canada converged rapidly with the U.S. during the post-war era, driven by rapid investment, sectoral change (the growth of high-value manufacturing, in particular), and a growing public sector. By 1985, we were no longer “poor northern cousins,” producing at about 95% of U.S. levels. That convergence has dramaticlaly reversed, despite America’s many problems in the intervening years. We’re back to 70% of U.S. levels, and still falling. The growing importance of non-renewable resource extraction, the contraction of manufacturing, and the growth of non-traded low-productivity sectors are the key drivers. This is a damning refutation of the assumption made by pro-FTA economists that continental integration would automatically harmonize productivity levels; in fact, integration (and Canada’s consequent pigeon-holing as resource producer) has had exactly the opposite effect.

2. Aggregate productivity in the business sector, measured in real outpupt per hour of work, relative to the U.S. This is a shocking graph, first published by Andrew Sharpe’s Centre for the Study of Living Standards (see his Table 6 here). International comparisons of productivity levels are rare (due to methodological difficulties in comparing value-added across currencies, and other data challenges). Canada converged rapidly with the U.S. during the post-war era, driven by rapid investment, sectoral change (the growth of high-value manufacturing, in particular), and a growing public sector. By 1985, we were no longer “poor northern cousins,” producing at about 95% of U.S. levels. That convergence has dramaticlaly reversed, despite America’s many problems in the intervening years. We’re back to 70% of U.S. levels, and still falling. The growing importance of non-renewable resource extraction, the contraction of manufacturing, and the growth of non-traded low-productivity sectors are the key drivers. This is a damning refutation of the assumption made by pro-FTA economists that continental integration would automatically harmonize productivity levels; in fact, integration (and Canada’s consequent pigeon-holing as resource producer) has had exactly the opposite effect.

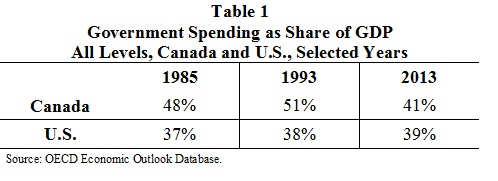

3. In the public sector, all three of my key dimensions of neoliberal transition have contributed to a retrenchment and refocussing of state activity. Neoliberalism does not necessarily imply a smaller state; its main goal is to reorient state activity in a manner that reinforces business power (collecting less taxes from corporations and the high-income individuals who own them; delivering more services that help business, like training and infrastructure; and providing less services that undermine business power, like income supports for working-age people). In Canada’s case, those have all occurred, but in the context of a general downsizing of state activity that is among the more dramatic in the capitalist world. Initially, the cold shock of monetarism meant higher state spending (back when most unemployed people could actually qualify for unemployment insurance). That changed beginning in the 1990s when the social welfare system was forcibly harmonized to fit better with the bitter new macroeconomic reality. Government spending as a share of GDP has declined by 10 points since 1993, and is now nearly harmonized with the U.S. FTA critics predicted that continental harmonization would inevitably lead to a form of social harmonization, and in aggregate this has been true — not because of provisions written into a trade deal, but because of the general economic and political forces which neoliberalism (including free trade) has unleashed. (Despite this general harmonization in the scale of public sector activity, of course, there are still important differences in social policies between Canada and the U.S. that we must fight to protect.)

3. In the public sector, all three of my key dimensions of neoliberal transition have contributed to a retrenchment and refocussing of state activity. Neoliberalism does not necessarily imply a smaller state; its main goal is to reorient state activity in a manner that reinforces business power (collecting less taxes from corporations and the high-income individuals who own them; delivering more services that help business, like training and infrastructure; and providing less services that undermine business power, like income supports for working-age people). In Canada’s case, those have all occurred, but in the context of a general downsizing of state activity that is among the more dramatic in the capitalist world. Initially, the cold shock of monetarism meant higher state spending (back when most unemployed people could actually qualify for unemployment insurance). That changed beginning in the 1990s when the social welfare system was forcibly harmonized to fit better with the bitter new macroeconomic reality. Government spending as a share of GDP has declined by 10 points since 1993, and is now nearly harmonized with the U.S. FTA critics predicted that continental harmonization would inevitably lead to a form of social harmonization, and in aggregate this has been true — not because of provisions written into a trade deal, but because of the general economic and political forces which neoliberalism (including free trade) has unleashed. (Despite this general harmonization in the scale of public sector activity, of course, there are still important differences in social policies between Canada and the U.S. that we must fight to protect.)

Feedback on my “three and three” analysis is most welcome, as are comparisons to the implementation of neoliberalism in other countries. And once again I highly recommend the whole CD compilation.

Feedback on my “three and three” analysis is most welcome, as are comparisons to the implementation of neoliberalism in other countries. And once again I highly recommend the whole CD compilation.

I think Keynesian-leaning economists need to make assertions like ‘free-market ideology didn’t deliver promised prosperity’ and then back it up with facts. It would appear the free-market reforms of the past 30 years have failed in every respect. When do we stop fooling around with theory and look at real world results? Especially when compared to the phenomenal success of the Keynesian post-war era?

Milton Friedman revived free-market ideology (which crashed and burned in the Great Depression,) by claiming the cause was all bad monetary policy (from which he developed monetarism.) Keynesians really need to explain the high inflation of the 1970s to revive the Keynesian system.

I believe the Keynesian model explains it well enough in simple terms: government policy used as a counterweight to the business cycle with fiscal, monetary and regulatory measures.

So during the Great Depression or presently during the Great Recession, the counterweight has to go heavy: big fiscal stimulus, zero-bound interest rates, perhaps raise the inflation target in the medium term.

During the 1970s, the counterweight had to go heavy in the other direction: austerity measures, high interest rates and a freeze on wages and strikes. Given the damage the Volcker Shock caused (and the heavy-handed disinflation measures of the 1990s,) we would’ve been better off using all government tools together to get a handle on it.

Over the past 30 years, the central banks have commandeered the economy on the absurd pretense of a technocracy that doesn’t exist. They made many mistakes including the attempt to eliminate the business cycle. But inflation targeting is really just Keynesian economics less the fiscal and regulatory measures. Therefore we would be better off with cooperation between government and the central bank to use all policies together to control the economy in the most efficient way possible.

given the transformations underway within the financial aspects of the economy- and the housing bubble and consumer credit paced growth strategy- I do think you might want to add into this the financialization of the economy- in fact I do think it might even be more important that the staples switch that Harper pushed us towards- especially oil.

The rational- can you imagine what the economy would look like right now if the neo-cons- given the failure of the economy under traditional wage led growth economics of capital, had not pumped up the housing sector- using the financialization aspects to help leverage the banks in their derivative trading and international pursuits of commidifying money outside the circuits of productive capital.

Think about that- they built an international process to print ficticious money and attach real value to it, control the world’s governments monetary policy and helped prop wages up to home owners- who were already mainly middle classed and very powerful in the electorate. What a beautiful piece of economic engineering to maintain control- that is if you happen to be a profit maximizer and political hegemon.

And I am not supporting the housing bubble- but I will say this- it saved the asses of the wealthy and might actually saved capitalism- or at least its demise into a slow rot into the abyss as the population gets eventually dragged onto a burning ship to the sun- sponsored by Coca-cola or is it Pepsi.

So I think you missed a massive piece there Jimbo. I would redefine number 3.